A 66-year-old, physically active, nondiabetic man with no symptoms was tested for coronary artery calcium (CAC) on the advice of his physician, who was debating whether to start him on a statin for an LDL-cholesterol level of 120 mg/dL. The patient’s CAC score was 2000.

In follow-up, exercise echocardiography was arranged. The patient’s resting heart rate was 77 bpm, and his resting BP was 127/63 mm Hg. He exercised for 7 minutes and achieved 109% of maximum predicted heart rate (169 bpm) and a normal exercise BP. His LV ejection fraction was >55% both before and after the stress test, although during stress he developed mild anterior hypokinesis. He experienced no chest pain during exercise, but the test was stopped because slight (<1 mm) ST-segment depressions were observed.

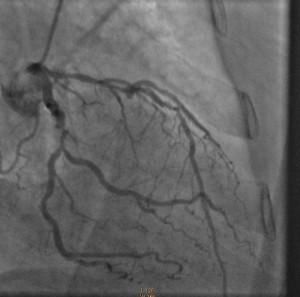

Cardiac catheterization revealed 80% to 90% proximal and mid-stenoses in the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, the left circumflex (LCX) artery, and the right coronary artery (RCA). TIMI 3 flow was noted throughout. The LAD and LCX arteries are shown in the left image below; the RCA is shown on the right.

Patients like this one have not been well studied in clinical trials, but his lack of diabetes, chest pain, heart failure, and functional limitations are positive prognostic signs that negate the severe CAD and coronary calcium burden.

Questions:

1. Given that the main goal is to reduce mortality risk, how would you extrapolate from the current literature to formulate the best plan for this patient? Would any potential mortality improvement from CABG, for example, justify the risks of surgery?

2. High-intensity statin therapy and lifestyle modification have been found to lead to plaque regression. Are these steps sufficient to lead to meaningful anatomical and/or functional changes that would reduce or eliminate any need for surgery? Do you know of any cases in which those steps have been sufficient?

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Response:

December 18, 2014

Questions:

1. Given that the main goal is to reduce mortality risk, how would you extrapolate from the current literature to formulate the best plan for this patient? Would any potential mortality improvement from CABG, for example, justify the risks of surgery?

The challenge is to modify this asymptomatic patient’s significantly increased risk for cardiovascular events (as predicated by his CAC and angiographic CAD). Several issues may be underappreciated at first glance:

- Extrapolation from the current literature is difficult because such asymptomatic patients have not been studied in large-scale contemporary randomized trials. In fact, the 1997 ACIP trial suggested that treatment of “asymptomatic ischemia” with revascularization was associated with lower risks for CV events and mortality than was medical management (without a statin).

- The evidence for provokable ischemia by stress testing without symptoms is suggestive of a defective physiologic warning system.

- Revascularization risk in a patient without significant comorbidities is quite modest but quantifiable: <0.5% to 1.0% mortality risk with either CABG or PCI.

Although I support an initial aggressive medical approach (see my NEJM editorial on STICH), close surveillance and acknowledgement of the limitations noted above should be reviewed with the patient. Repeat exercise testing to assess the efficacy of treatment on ischemia would be reasonable as well. Some patients will cross over to revascularization (30% in ACIP); others will elect to be revascularized initially, which I have supported in my practice as well.

2. High-intensity statin therapy and lifestyle modification have been found to lead to plaque regression. Are these steps sufficient to lead to meaningful anatomical and/or functional changes that would reduce or eliminate any need for surgery? Do you know of any cases in which those steps have been sufficient?

In addition to plaque regression, high-intensity statin therapy improves coronary endothelial function and reduces the biologic susceptibility to plaque rupture, a predominant mechanism of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. It is likely that such changes, rather than a reduction in severity stenosis per se, produce the 30% to 40% reduction in cardiovascular outcomes seen in statin trials. Many cardiologists, myself included, have anecdotal experiences successfully managing large-burden CAD with aggressive medical management (but bear in mind that achieving optimal outcomes requires aggressive lipid lowering, treatment of ischemia, optimized management of comorbidities, and close patient surveillance).

Follow-Up:

December 24, 2014

After discussion with his physicians and family, the patient opted for an initial intervention involving aggressive medical therapy and lifestyle changes. He is currently taking aspirin 81 mg, metoprolol 25 mg twice daily, lisinopril 2.5 mg daily, and atorvastatin 40 mg daily — and he undergoes cardiac rehabilitation 5 days per week. He has been a lifelong vegetarian, but in addition he is now reducing his consumption of refined carbohydrates and sugars. After completing cardiac rehabilitation, he will undergo another stress test to assess his functional capacity, symptoms at peak exercise, and ischemia burden.